Psychedelic Therapy

- A List of Books for Psychedelic Therapy and Exploration

Please use Bookshop.org instead of Amazon if you decide to purchase any of these books. Amazon is an unethical company, and we should all make an effort to give them less money.

Having said that, there are two books that should make this list, but they are only available on Amazon:

- Psychedelic Drug Reduces Anxiety by Targeting Fast-spiking Interneuronsneurosciencenews.com Psychedelic Drug Reduces Anxiety by Targeting Fast-spiking Interneurons - Neuroscience News

The psychedelic DOI, a compound similar to LSD, reduced anxiety in mice by activating specific brain cells called fast-spiking interneurons.

- What I Wish I’d Known Before Ketamine Therapypsychedelic.support What I Wish I’d Known Before Ketamine Therapy Psychedelic Support

Ketamine therapy is incredibly promising for the treatment of depression. Olivia Clear, APCC helps you prepare for your ketamine therapy.

- High-dose psilocybin treats depression more effectively than the SSRI, escitalopram (aka Lexapro)www.pharmexec.com Study Suggests Promise of Psilocybin in Treating Depressive Symptoms

Findings from a recent study demonstrated that high-dose psilocybin provided a superior reduction in depressive symptoms compared to both placebo and escitalopram in patients with major depressive disorder.

- LSD reshapes the brain's response to pain, neuroimaging study findswww.psypost.org LSD reshapes the brain's response to pain, neuroimaging study finds

LSD alters brain activity and connectivity in key regions associated with pain processing, offering potential insights for pain management and the therapeutic use of psychedelics.

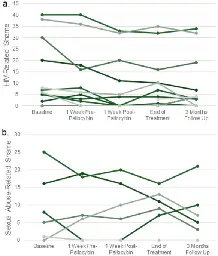

- Receiving psilocybin-assisted group therapy was associated with a large decrease in HIV-related shamewww.nature.com Psilocybin-assisted therapy and HIV-related shame - Scientific Reports

As a proposed mediator between stigma-related stressors and negative mental health outcomes, HIV-related shame has been predictive of increased rates of substance use and difficulties adhering to antiretroviral treatment among people with HIV. These downstream manifestations have ultimately impeded ...

- LSD-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety: patients sustained improvements for a yearwww.cambridge.org LSD-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety: open-label prospective 12-month follow-up | The British Journal of Psychiatry | Cambridge Core

LSD-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety: open-label prospective 12-month follow-up

- 10 Great Sources of Art to Pair With Psychedelic Mushroomsdoubleblindmag.com 10 Great Sources of Art to Pair With Psychedelic Mushrooms

Next time you find yourself lost in a psychedelic trip, gaze upon this art inspired by the colorful, vibrant world of mushrooms.

- Brain imaging study sheds light on how magic mushrooms paint vivid images behind your eyelidswww.psypost.org Brain imaging study sheds light on how magic mushrooms paint vivid images behind your eyelids

Neuroimaging research has found that psilocybin increases self-inhibition in visual brain regions and enhances top-down connectivity, leading to vivid, internally generated visual imagery with eyes closed.

- The science of magic mushrooms: Fascinating findings from 7 new studies of psilocybinwww.psypost.org The science of magic mushrooms: Fascinating findings from 7 new studies of psilocybin

In recent years, the resurgence of interest in psychedelic substances has spotlighted psilocybin as a potential breakthrough in mental health treatment.

- Psilocybin enhances exploratory behavior without impairing learningwww.psypost.org Psilocybin enhances exploratory behavior without impairing learning

Psilocybin, found in "magic mushrooms," does not impair learning and may enhance exploration. Higher doses improved learning rates, especially with certain cues, suggesting potential cognitive benefits in therapeutic settings.

- Older adults who have used psychedelics tend to have better executive functioningwww.psypost.org Older adults who have used psychedelics tend to have better executive functioning

Psychedelic use is linked to better cognitive functioning and fewer depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults, according to a recent study.

- Coming back together: a qualitative survey study of coping and support strategies used by people to cope with extended difficulties after the use of psychedelic drugswww.frontiersin.org Frontiers | Coming back together: a qualitative survey study of coping and support strategies used by people to cope with extended difficulties after the use of psychedelic drugs

IntroductionA growing body of literature is investigating the difficulties that some individuals encounter after psychedelic experiences. Existing research h...

- Long-term ayahuasca use is associated with preserved global cognitive function and improved memorylink.springer.com Long-term ayahuasca use is associated with preserved global cognitive function and improved memory: a cross-sectional study with ritual users - European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience

Although several studies have been conducted to elucidate the relationship between psychedelic consumption and cognition, few have focused on understanding the long-term use influence of these substances on these variables, especially in ritualistic contexts. To verify the influence of ritualistic a...

- Psychedelics could treat some of the worst chronic pain in the worldwww.vox.com Psychedelics could treat some of the worst chronic pain in the world

Decades of citizen science are finally translating into clinical trials for psychedelic pain treatments.

- Chemical tweaks to a toad hallucinogen turns it into a potential drugarstechnica.com Chemical tweaks to a toad hallucinogen turns it into a potential drug

Targets a different serotonin receptor from other popular hallucinogens.

See also: Family Guy S02E14 Let’s Go to the Hop

- Psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depression increases psychological flexibilitywww.nature.com Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depression: results from an exploratory placebo-controlled trial - Scientific Reports

Several phase II studies have demonstrated that psilocybin-assisted therapy shows therapeutic potential across a spectrum of neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder (MDD). However, the mechanisms underlying its often persisting beneficial effects remain unclear. Observationa...

>Psychological flexibility is a multifaceted construct composed of: > >(1) openness to experience (experiential acceptance); > >(2) behavioral awareness (i.e., mindful attention to the present moment); and > >(3) values-driven action

- Psychedelic medicine gets a boost (MDMA for PTSD being reviewed by the FDA)

> Lykos’ application is for talk therapy combined with MDMA, commonly called ecstasy, as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. > >The FDA granted the application priority review, meaning the agency will review it over six months instead of the standard 10-month timeline. The agency set a target date of Aug. 11 to decide whether to approve the application. > >The August target date isn’t the end of the line. Should the FDA approve Lykos’ application, the Drug Enforcement Administration must reschedule MDMA before doctors can prescribe it.

- Positive initial data from study of novel 5-MeO-DMT (DMT) for treatment-resistant depressionwww.businesswire.com Beckley Psytech announces positive initial data from Phase IIa study of novel 5-MeO-DMT formulation BPL-003 for Treatment Resistant Depression

Beckley Psytech Ltd, the private, clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company dedicated to improving the lives of people living with neuropsychiatric dis

TL;DR:

-

A single dose of DMT produced a fast antidepressant response in 55% of patients the day after dosing.

-

A durable antidepressant effect was also shown, with 55% of patients in remission from depression at day 29 and 45% in remission at day 85.

-

DMT demonstrated a short treatment duration, with acute effects resolving and patients deemed dischargeable within an average time of less than 2 hours.

-

DMT was generally well-tolerated with no serious adverse events reported.

-

- An inside look at what happens during a psychedelic therapy session in Colorado

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

- Utah Governor Lets Psychedelics Pilot Program Bill Become Law Without His Signature, Citing 'Overwhelming Support'www.marijuanamoment.net Utah Governor Lets Psychedelics Pilot Program Bill Become Law Without His Signature, Citing 'Overwhelming Support' - Marijuana Moment

The Republican governor of Utah has allowed a bill to become law without his signature that authorizes a pilot program for hospitals to administer psilocybin and MDMA as an alternative treatment option. Gov. Spencer Cox (R) said in a letter to legislative leaders last week that he was letting the ps...

The Republican governor of Utah has allowed a bill to become law without his signature that authorizes a pilot program for hospitals to administer psilocybin and MDMA as an alternative treatment option.

- Alberta Blue Cross is the first insurance provider in Canada to cover psychedelic-assisted therapywww.prnewswire.com ATMA CENA Celebrates Groundbreaking Support from Alberta Blue Cross for Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies

/PRNewswire/ - ATMA CENA Psychedelic Healthcare Solutions (PHS) is a collaboration of ATMA Journey Centers Inc. ("ATMA"), Cena Life Inc. and partners across...

> Initially focusing on ketamine-assisted therapy, this coverage is designed to include psilocybin and MDMA once they are legalized for therapy in Canada.

- Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy for Complex PTSD (A Single-Subject Case Study)

Abstract:

Current research suggests that ketamine-assisted psychotherapy has benefit for the treatment of mental disorders. We report on the results of ketamine-assisted intensive outpatient psychotherapeutic treatment of a client with treatment-resistant, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of experiences of racism and childhood sexual abuse.

The client’s presenting symptoms included hypervigilance, social avoidance, feelings of hopelessness, and intense recollections. These symptoms impacted all areas of daily functioning.

Psychoeducation was provided on how untreated intergenerational trauma, compounded by additional traumatic experiences, potentiated the client’s experience of PTSD and subsequent maladaptive coping mechanisms.

Ketamine was administered four times over a 13-day span as an off-label, adjunct to psychotherapy. Therapeutic interventions and orientations utilized were mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP).

New skills were obtained in helping the client respond effectively to negative self-talk, catastrophic thinking, and feelings of helplessness. Treatment led to a significant reduction in symptoms after completion of the program, with gains maintained 4 months post-treatment.

This case study demonstrates the effective use of ketamine as an adjunct to psychotherapy in treatment-resistant PTSD.

- Psychological experiences underlie psilocybin therapy's success: Mystical experiences and ego dissolution identified as key mediatorswww.psypost.org Psychological experiences underlie psilocybin therapy's success: Mystical experiences and ego dissolution identified as key mediators

A groundbreaking study sheds light on psilocybin therapy's success in treating depression, highlighting the crucial roles of mystical experiences and ego dissolution, enhanced by music, in surpassing traditional treatments. The findings were published in the International Journal of Mental Health an...

- Psilocybin from "magic" mushrooms weakens the brain's response to angry faceswww.psypost.org Psilocybin from "magic" mushrooms weakens the brain's response to angry faces

A study revealed psilocybin diminishes the amygdala response to angry faces, potentially impacting emotion processing. This discovery underscores its potential for treating conditions like depression and anxiety, highlighting the profound effects of psychedelics on the brain.

- Complex PTSD & Psychedelicspsychedelicchronicles.earth Complex PTSD & Psychedelics — Psychedelic Chronicles

Woven together by several threads of trauma, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) can paralyze a person’s mind in places of darkness. Could psychedelic therapy present a way out?

>In a recent study, a group of scientists investigated adults who had been victims of childhood abuse. Through collecting data from various questionnaires, they compared symptoms of C-PTSD between those who had used psychedelics in an intentional therapeutic way, with those who hadn’t. > >The scientists found that adults who had used psychedelics multiple times with therapeutic intent had lower scores on a DSO scale - a measure of C-PTSD core features including low self-worth, problems with regulating emotions, and difficulties in relationships. Their results also showed those who had an increased number of intentional psychedelic uses revealed decreased levels of self-shame, another common C-PTSD symptom.

- Single dose of LSD provides immediate, lasting anxiety relief, study sayswww.cnn.com Single dose of LSD provides immediate, lasting anxiety relief, study says | CNN

One dose of LSD in a clinical trial significantly improved anxiety and lasted for 12 weeks, convincing the FDA to give the drug a breakthrough therapy designation.

- Microdosing Psychedelics Could Help People With ADHDwww.vice.com Microdosing Psychedelics Could Help People With ADHD

A new study shows that consuming tiny amounts of LSD or magic mushrooms could help ADHD sufferers with mindfulness.

- Great Expectations: recommendations for improving the methodological rigor of psychedelic clinical trialswww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov Great Expectations: recommendations for improving the methodological rigor of psychedelic clinical trials

Psychedelic research continues to garner significant public and scientific interest with a growing number of clinical studies examining a wide range of conditions and disorders. However, expectancy effects and effective condition masking have been raised ...

The gold standard in the context of medical trials is the double-blind randomized trial. In such trials, the response to a potential therapeutic agent is measured relative to the response to an inactive placebo.

Psychedelics are thought to be powerful therapeutic agents. Some psychedelics may be therapeutic even at sub-perceptual doses, but it is likely that some therapeutic benefit can be obtained at psychoactive doses, and - in some cases - the psychoactive experience itself may contribute to the therapeutic effect.

The problem that this review addresses is: How do you run a blind trial with a placebo when the "active" ingredient is expected to produce a psychoactive experience? Participants are by definition not supposed to know whether they took the placebo or the active agent... but someone who experiences a powerful psychoactive experience is unlikely to remain "blind".

The review goes over some ideas such as the use of "active placebo comparators" which are psychoactive substances that are different enough to the substance under test.

An argument is also made for a paradigm shift: let's move away from double blinded placebo trials as the global gold standard and establish alternative methods to show efficacy - such as "pragmatic clinical trial designs".

I was going through the literature and thought this was an interesting topic to share and discuss. What do you think? 😄

- How psilocybin, the psychedelic in mushrooms, may rewire the brain to ease depression, anxiety and morewww.cnn.com How psilocybin, the psychedelic in mushrooms, may rewire the brain to ease depression, anxiety and more | CNN

Scientists are learning more about how psychedelic mushrooms may alter the brain, potentially leading to long-lasting reversals of depression, anxiety, cluster headaches and more.

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.world/post/12684314

> How psilocybin, the psychedelic in mushrooms, may rewire the brain to ease depression, anxiety and more

- Ketamine as a vaccine for depression (2024)bigthink.com A vaccine for depression

A researcher explains the new ketamine trials in patients with depression, and why they show more promise than traditional anti-depressants.

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.world/post/10996654

> Ketamine’s remarkable effect bolsters a new theory of mental illness.

- Inside psychedelic-assisted therapy: How exactly does it work?www.cbsnews.com Inside psychedelic-assisted therapy: How exactly does it work?

After veterans went through FDA-approved trials with other psychedelic drugs, two-thirds no longer had PTSD. Several of these trials are happening in the U.S. now.

Inside a spa-like room at the Institute for Integrative Therapies (ITT) in Eden Prairie are four recliners, several sets of headphones and eye coverings.

They are there for when patients embark on what ITT's founder, Dr. Manoj Doss, calls their psychedelic journey. The chairs are reclined, the eye coverings go on, the music is piped in and the psychedelic is then given, via lozenge or injection.

"The reason is we want to make this completely introspective," said Dr. Doss. "There's no external stimuli that is affecting their journey and they completely inwards towards it."

A facilitator therapist sits in the room with the patients to guide them through rough spots or help them with anything they want to bring up. Dr. Doss is always nearby, just in case there are side effects, like nausea, headaches or dizziness.

But, this journey begins long before any patient ever receives a psychedelic drug. At this clinic – the first of its kind in Minnesota – that drug is ketamine, the only legal psychedelic in the state. Ketamine was created as an anesthetic in the 1970s, but at lower doses, it can produce psychedelic states.

Before being administered the ketamine, patients first required to go through a medical assessment that includes looking at any cardiovascular problems or history of mania or psychosis. Those histories might make them ineligible for this kind of therapy. After that, patients must undergo three to five psychotherapy sessions to prepare to talk about what issues they want to address and what they hope the gain from the experience. Following the medication, patients continue with their therapy with a hope to find a breakthrough, changes in behavior, or shifts in perceptions.

"The psychedelic is not the cure itself," said Dr. Doss. "The psychedelic is the catalyst or the mediator."

In an interview with CBS News, former Marine Scott Ostrom told CBS' David Martin that using psychedelics in therapy allowed him to open up and peel away the layers of trauma. He credits the psychedelic treatment and therapy with getting rid of panic attacks and thoughts of suicide. Ostrom had been part of a large trial involving the psychedelic drug MDMA.

These trials, conducted by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, found two-thirds of people using this treatment no longer reported symptoms of PTSD. They are in the final stage of research required by the Food and Drug Administration and just one of several FDA-approved trials involving the use of therapeutic use of psychedelics.

"After those three MDMA sessions," Ostrom said, "I haven't had a nightmare about the war since."

Dr. Voss said there are several thoughts and theories about how psychedelics affect the human brain, but the prevailing one has to do with the brain creating new circuits and connections. Essentially, they can help un-stick "stuck" thoughts, like ruminations, self-doubt, obsessions or compulsions. That then gives the psychotherapy, he said, a better chance of being successful.

"What psychedelics can do is basically shake up a snow globe and give you a fresh set of powder to ski on," Dr. Doss.

Most psychedelics have been illegal in the U.S. since the 1970s, but there are several drugs, including MDMA and psylocibin, that are expected to apply for approval to the FDA.

"In the right setting with the right provider, it's an extraordinarily important tool," said Dr. Doss. "It's not just for the mentally ill, it's for everyone in between that just wants a better life."

- Momentum builds for psychedelic therapies for troops, vetswww.timescall.com Momentum builds for psychedelic therapies for troops, vets

Current legislative proposals include studies of the effectiveness of using psychedelics to treat PTSD among active-duty servicemembers and veterans, reflecting a small but significant shift among …

In 2004, Mike Gemignani enlisted in the Army after graduating from high school. A forward observer, he directed artillery units and Apache attack helicopters to their targets during his two tours in Iraq with the 101st Airborne Division.

He eventually left the military, went to college and settled into a job. But a slow trickle of anxiety and depression soon followed.

He sought help through the Department of Veterans Affairs, where counselors prescribed him “fistfuls” of medication, including opioids and more drugs to counter their side effects. The drugs didn’t help his depression, and for days at a time he would do nothing, immobilized by the illness.

Gemignani’s story is not uncommon for those who served in the military. But now, after years of effort, momentum is building in Congress to explore a new path for servicemembers and veterans struggling with psychological illnesses: psychedelics.

Current legislative proposals include studies of the effectiveness of using psychedelics to treat PTSD among active-duty servicemembers and veterans, reflecting a small but significant shift among lawmakers’ attitudes toward therapeutic use of the drugs.

But psychedelic therapy was not an option when Gemignani turned to the VA, and his mental status continued to deteriorate.

“I got to the point where I was sitting in my basement office with a pistol in my hand,” Gemignani said.

Gemignani’s situation changed when his wife found a website for the organization Veterans of War, a nonprofit that facilitates six-month programs for veterans who, having exhausted their other options, travel overseas in an effort to treat their depression, anxiety and PTSD with psychedelics.

The program includes months of coaching, therapy and community-building, but is centered around a weeklong trip, typically to the jungles of Peru or Costa Rica, where participants take ayahuasca, a powerful psychoactive brew traditionally used by indigenous cultures that, among other psychedelics, is gaining popularity in the U.S. as a way to treat psychological issues without turning to opioids.

But psychedelic substances like ayahuasca and psilocybin — commonly referred to as magic mushrooms — are illegal in the U.S., forcing interested Americans to seek them out in more permissive nations overseas, or find them on the black market.

“That’s the irony. You have veterans who have done so much for our country yet, when we find a cure, they have to leave the country to get cured,” said Rep. Lou Correa, D-Calif., who co-chairs the Congressional Psychedelics Advancing Therapies (PATH) Caucus alongside Rep. Jack Bergman, R-Mich.

Therapeutic value

Attitudes toward the substances in the U.S., and on Capitol Hill, are slowly shifting.

Proponents say psychedelics offer a long-term alleviation of symptoms, if not cures, to some psychological illnesses, sometimes after a single use.

The Food and Drug Administration has previously granted “breakthrough therapy” designations to psilocybin and MDMA, another psychedelic, commonly referred to as ecstasy or Molly. The designation recognizes the therapeutic potential of the drugs, and can eventually lead to their approval.

Full approval for MDMA is widely expected in the coming months, and psilocybin may not be far behind.

Researchers have compared the effects of psychedelics on a person’s brain to fresh snowfall on a heavily used ski slope. Once the new snow has fallen, new paths — or thought patterns — can be created. Those new thought patterns may play an important role in overcoming illnesses like PTSD.

Jesse Gould, a former Army Ranger and founder of the Heroic Hearts Project, another nonprofit that facilitates access to psychedelic programs for veterans, says his organization has served over 850 veterans and 100 spouses.

When combined with all of the other groups in the space, that figure is likely over 3,000. And when that figure is combined with the number of veterans who go it alone, it’s likely over 5,000, Gould estimated.

Legislative efforts

With Congress back from Thanksgiving recess, House and Senate lawmakers are set to begin formal conference negotiations on the fiscal 2024 Pentagon policy bill.

Among the thousands of proposals that members will wade through is one by Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Daniel Crenshaw, R-Texas, that would direct the Defense Department to study the use of psychedelics in the treatment of PTSD and other related illnesses in active duty servicemembers.

If included in the final version of the bill and passed into law, the provision would be a first for the Defense Department. It’s something Ocasio-Cortez has advocated for since 2019, when she tried unsuccessfully (91 for, 331 against) to attach a similar amendment to an appropriations package.

“Every time we bring this issue up we gain ground. When I first introduced an amendment on this, people were laughing at it. Fast forward a couple of years and it’s now actually taken very, very seriously,” Ocasio-Cortez said in an interview.

According to Ocasio-Cortez, that unsuccessful vote four years ago sparked national interest in the issue.

“When people saw how out of step Congress was with the general public on this issue, that’s when we started seeing the outpouring of support from veterans and survivors of sexual trauma,” she said.

In the days following the vote, members not only approached Ocasio-Cortez to apologize, she said, but subsequently changed their positions. And the issue has attracted champions on both sides of the aisle.

At a news conference earlier this year, Crenshaw, a conservative, acknowledged his unlikely pairing with Ocasio-Cortez, one of the most progressive members of Congress. “This is a wild coalition, okay?” Crenshaw said.

“But everybody’s on the same page because there’s a realization that these therapies are working. There’s already some pretty solid studies, specifically on MDMA, that show just unbelievable outcomes — massive reductions in PTSD symptoms. We need to keep replicating those studies,” he said.

And other psychedelics-related pieces of legislation are also working their way through Congress.

In July, Bergman and Correa successfully offered an amendment to the fiscal 2024 Military Construction-VA appropriations bill that pushed the VA to carry out “large-scale studies” into drugs like psilocybin and MDMA.

This month, Carolyn Clancy, VA assistant undersecretary for health for discovery, education, and affiliate networks, told the House Veterans’ Affairs Subcommittee on Health that her agency is conducting several studies on the topic.

Changing attitudes

Correa and Bergman, a former Marine Corps lieutenant general and the highest-ranking combat veteran to serve in the House, have been working to bring awareness to the possibilities surrounding psychedelics.

As co-chairs of the PATH Caucus, the pair hold regular briefings with lawmakers, inviting those who they feel “will have an open mind” toward new applications for psychedelics.

In an interview, Bergman described one such briefing also attended by veterans who had found success in treating their illnesses with psychedelics.

“We brought in veterans who had gone to Mexico to get the treatment, and it was powerful. There’s no other word. And I had a few members who said they couldn’t thank us enough because it opened their eyes,” Bergman said.

Bergman and Correa both said they felt a shift in momentum among lawmakers as, little by little, more members come around to seeing psychedelics in a positive light.

House Armed Services ranking member Adam Smith, D-Wash., who has talked publicly about his own experiences in psychotherapy to overcome chronic anxiety, said he was supportive of the push in Congress to study the drugs, but that non-pharmaceutical options should also be considered by those seeking treatment.

“I think [the legislation] makes sense,” he said, “but you’re messing with some pretty complicated stuff and introducing drugs into that. It’s worth pursuing, but it’s also worth aggressively pursuing some non-pharmaceutical options.”

But Senate Armed Services Chairman Jack Reed, D-R.I., foreshadowed possible headwinds in his chamber.

“Generally speaking, a study of a serious subject like this is something we would include in the NDAA, but it’s a new topic and for some people it may be the first they’ve heard about it,” Reed said in an interview.

That hesitancy could mean that the provision from Ocasio-Cortez and Crenshaw is dropped from the final version of the bill. Even if that were to happen, however, it appears clear that momentum for the study and use of psychedelics in the U.S. is steadily building, and other avenues besides the NDAA exist.

Brett Waters, the founder of Reason for Hope, an organization that advocates for access to so-called psychedelic medicine and assisted therapies, said the last few years have shown a clear shift toward understanding and acceptance of psychedelics in the U.S.

“The way people describe psychedelics is unlike the way they talk about any other therapy,” Waters said. “They say it was life changing, or one of the most meaningful things to ever happen to them. And as more legislators are hearing those stories from veterans and others it’s having an incredibly compelling effect.”

- A new chapter in the science of psychedelic microdosing: A study on rats offers the first evidence that small doses of hallucinogenic drugs could have therapeutic benefits.www.theatlantic.com A New Chapter in the Science of Psychedelic Microdosing

A study on rats offers the first biological evidence that small doses of hallucinogenic drugs could have therapeutic benefits.

The purported benefits of microdosing psychedelics are as numerous as the research is sparse. The technique, which involves ingesting small amounts of LSD, mushrooms, or other hallucinogenic drugs every three or four days, has made headlines for its popularity as a “productivity hack” among the Silicon Valley elite.

But anecdotal endorsements of microdosing claim that the routine can lead to a whole variety of benefits, including heightened emotional sensitivity, athletic performance, and creativity; and relief from symptoms of anxiety, depression, OCD, PTSD, and chronic pain—all without resulting in any sort of trip.

In a lab setting, meanwhile, these effects have hardly been studied. Microdosing straddles a line between homeopathic remedy and experimental biohacking as a promising tool that hasn’t yet made its way through the clinical system’s rigorous checks and balances. Now a new study published Monday in the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience provides the first biological evidence that psychedelic microdosing could have unique therapeutic effects that differ from the effects of a full dose.

For David Olson, a professor in the chemistry and neuroscience departments at the University of California at Davis and one of the paper’s authors, it started with ketamine. Over the past few years, Olson watched as the formerly notorious anesthetic cum party drug was rebranded as an experimental miracle for treatment-resistant depression.

Ketamine has the ability to rebuild fraying connections between brain cells integral to networks that regulate emotions and mood, thanks to an effect known as neural plasticity. Olson suspected that the process by which ketamine promotes this type of plasticity could be activated by other substances as well, and in June his team published a paper showing that in rats, psychedelics such as LSD, ecstasy, and dimethyltryptamin, or DMT, mirror ketamine’s effects.

When the study ended, Olson began to wonder if the therapeutic benefits could also be achieved through microdosing. Along with the hallucinogenic effects of the drugs, he’d found that standard doses gave his rats fierce anxiety, which seemed like a high price to pay for an effective antidepressant. “I really wanted to answer the question as to whether or not the hallucinogenic effects of these compounds were necessary for the therapeutic effects,” Olson says.

At that point, there had only been four published studies on microdosing: three based on interviews with anonymous users who reported the effects, and one write-up of a conference where attendees ingested psychedelic truffles. (A fifth microdosing study, also interview-based but the first with an empirical setup, was published last month in the journal PLOS One.)

For the new study, Olson’s team calculated a dosage of DMT—which is chemically like a stripped-down version of LSD or psilocybin “magic” mushrooms—that was too small to produce any hallucinogenic effects. They gave it to the rats every three days. On off days, the animals completed tests, including two experimental proxies for human anxiety and depression, respectively: a repetitive fear exercise, and a forced-swim test that looks at whether the animal will simply give up when in danger.

Seven weeks later, the researchers found that even though the rats weren’t given enough DMT to hallucinate, their depression and anxiety scores still improved significantly. The uptick in anxiety associated with the higher dose of DMT was nowhere to be found in the rats that had taken intermittent microdoses. Olson says the study demonstrates that the therapeutic effects of psychedelics—in rats, at least—can indeed be harnessed independently of the hallucinogenic effects. It appears that each of DMT’s distinct effects can be activated only if the amount of the drug present crosses a certain threshold. For the benefits of neural plasticity, that threshold seems to be lower.

For most substances, a study like this could quickly prompt more research that would eventually open the door to clinical trials. But for psychedelics, which are highly illegal substances in the United States that fall among the most strictly regulated both in and out of labs, the progression of research can be slower.

“There has been a very big transformation of how psychedelics are perceived in society over the past 10 years,” says Balazs Szigeti, a researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who is currently collecting data for a self-blinding study of microdosing. “Animal-model research is helpful in moving it forward, but the major hurdle to conducting a large-scale clinical study on microdosing is the money.”

In the 1950s and ’60s, tons of research funding in the United States and abroad was dedicated to studying the effects that psychedelics have on consciousness, creativity, and spirituality. But psychedelics were outlawed under President Richard Nixon’s Controlled Substances Act. Grant money for psychedelics research quickly dried up, and by the time researchers decades later became curious about the esoteric substances, most prior research had been rendered effectively useless by modern scientific standards. Grant money can still be hard to come by.

Noah Sweat, a program coordinator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Public Health, claims that the specter of this politicization continues to influence psychedelics research. “People now that are in positions of authority, either over departments that would be researching [psychedelics] or over the grant-awarding processes, might not have any sort of political objection to the research, but just have kind of absorbed the ambient cultural attitude toward them,” he says.

Still, psychedelics have potential dangers. When Olson’s team first gave rats standard, non-micro doses of psychedelics, one potential benefit they observed was a boost in the growth of dendritic spines—small protrusions that boost the activity of communicatory cells—in the part of the brain that controls personality and social behavior.

The team expected to see the same effect from a microdose, but instead found almost the opposite. “In the male rats, we saw no change in neuronal structure; and in the females, we actually saw a decrease in dendritic-spine density,” Olson says. To his team, these results were concerning: In some cases, it looked almost like the DMT was having a cytotoxic effect, proving fatal to brain cells.

Olson hopes that by experimentally adjusting different elements of the study, he can figure out a safe way to determine the boundaries of microdosing’s benefits and harms. One factor he’s especially interested in looking into is age, which he says can greatly limit the degree to which a boost in neural plasticity is helpful. Microdosing “during neurodevelopment could be really, really bad,” Olson explains. “On the other hand, the aging brain is a little more susceptible to issues of cytotoxicity, and so that also could be very, very bad. There could be only a very narrow window of time in which they might work.”

Maybe microdosing is the perfect answer for treatment-resistant depression between the ages of 30 and 40, but harmful at any other age. The idea that a tiny psychedelic dose could damage the same brain structures that a full dose reinforces feels counterintuitive, but might be something committed microdosers should consider. So much of what is understood about how various substances work presumes a sort of graded spectrum of effects. Could microdosing, which we still know so little about, be an exception to the rule?

“There’s that saying,” Olson says, “that the difference between a medicine and a poison is the dose.”

- A pilot study shows a single dose of psilocybin can significantly improve symptoms of SSRI-resistant body dysmorphic disorder for at least 12 weekspubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov Pilot study of single-dose psilocybin for serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant body dysmorphic disorder - PubMed

This study provides promising preliminary support for psilocybin as a treatment of BDD, warranting future controlled studies.

Abstract

Objective: Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is an often-severe condition in which individuals are preoccupied by misperceptions of their appearance as defective or ugly. Only serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive-behavioral therapy have been demonstrated efficacious in randomized controlled trials. Psilocybin is a psychedelic drug with growing evidence for safety and efficacy in treatment of depression. This study aimed to pilot test the feasibility, tolerability, safety, and efficacy of psilocybin treatment of adults with BDD.

Methods: In this open-label trial, 12 adults (8 women, 4 men) with moderate-to-severe non-delusional BDD that had been unresponsive to at least one serotonin reuptake inhibitor trial received a single oral dose of psilocybin 25 mg. There was no control group. Psychological support was provided before, during, and after the dosing session. The primary outcome measure for efficacy was the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale Modified for BDD (BDD-YBOCS) score during 12 weeks of assessments after dosing.

Results: All participants completed dosing and all follow-up assessments. BDD-YBOCS scores decreased significantly over 12 weeks of follow-up (p < .001) with a large effect size (partial eta squared = 0.54), and significant changes from baseline were present at week 1 and persisted through week 12. Secondary efficacy measures of BDD symptoms, conviction of belief, negative affect, and disability also improved significantly, and no serious adverse events occurred. At week 12, seven participants (58%) were rated responders, based on ≥30% decrease in BDD-YBOCS.

Conclusion: This study provides promising preliminary support for psilocybin as a treatment of BDD, warranting future controlled studies.

- My Adventures With the Trip Doctors: The Researchers and Renegades Bringing Psychedelic Drugs Into The Mental Health Mainstream by Michael Pollan (Long)www.nytimes.com My Adventures With the Trip Doctors (Published 2018)

The researchers and renegades bringing psychedelic drugs into the mental health mainstream.

My first psilocybin journey began around an altar in the middle of a second-story loft in a suburb of a small city on the Eastern Seaboard. On this adventure I would have a guide, a therapist who, like an unknown number of other therapists administering psychedelics in America today, must work underground because these drugs are illegal.

Seated across the altar from me, Mary (who asked that I use a nickname because of the work she does) began by reciting, with her eyes closed, a long and elaborate prayer derived from various Native American traditions. My eyes were closed, too, but now and again I couldn’t resist peeking out for a glance at my guide: a woman in her 60s with long blond hair parted in the middle and high cheekbones that I mention only because they would, in a few hours, figure in her miraculous transformation into a Mexican Indian.

I also stole a few glances at the scene: the squash-colored loft with its potted plants and symbols of fertility and female power; the embroidered purple fabric from Peru that covered the altar; and the collection of items arrayed across it, including an amethyst in the shape of a heart, a purple crystal holding a candle, a bowl containing a few squares of dark chocolate, the personal “sacred item” that Mary had asked me to bring (a little bronze Buddha a friend brought me from Tibet) and, set squarely before me, an antique plate holding the biggest psilocybin mushroom I had ever seen.

The crowded altar also held a branch of sage and a stub of palo santo, a fragrant wood that some Indians in South America burn ceremonially, and the jet-black wing of a crow. At various points in the ceremony, Mary would light the sage and the palo santo, using the crow’s wing to “smudge” me with the smoke — guiding the spirits through the space around my head.

The whole scene must sound ridiculously hokey, not to mention laced with cultural appropriation, yet the conviction Mary brought to the ceremony, together with the aromas of the burning plants and the spooky sound of the wing pulsing the air around my head — plus my own nervousness about the journey in store — cast a spell that allowed me to suspend my disbelief.

Mary trained under one of the revered “elders” in the psychedelic community, an 80-something psychologist who was one of Timothy Leary’s graduate students at Harvard. But I think it was her manner, her sobriety and her evident compassion that made me feel sufficiently comfortable to entrust her with, well, my mind.

As a child growing up outside Providence, R.I., Mary was an enthusiastic Catholic, she says, “until I realized I was a girl” — a fact that would disqualify her from ever performing the rituals she cherished. Her religiosity lay dormant until, in college, friends gave her a pot of honey infused with psilocybin for her birthday; a few spoonfuls of the honey “catapulted me into a huge change,” she told me the first time we met. The reawakening of her spiritual life led her onto the path of Tibetan Buddhism and eventually to take the vow of an initiate: “ ‘To assist all sentient beings in their awakening and enlightenment.’ Which is still my vocation.”

And now seated before her in her treatment room was me, the next sentient being on deck, hoping to be awakened. She asked me to state my intention, and I answered: to learn whatever the “mushroom teachers,” as she called them, could teach me about myself and about the nature of consciousness.

PSYCHEDELIC THERAPY, whether for the treatment of psychological problems or as a means of facilitating self-exploration and spiritual growth, is undergoing a renaissance in America. This is happening both underground, where the community of guides like Mary is thriving, and aboveground, at institutions like Johns Hopkins, New York University and U.C.L.A., where a series of drug trials have yielded notably promising results.

I call it a renaissance because much of the work represents a revival of research done in the 1950s and 1960s, when psychedelic drugs like LSD and psilocybin were closely studied and regarded by many in the mental health community as breakthroughs in psychopharmacology.

Before 1965, there were more than 1,000 published studies of psychedelics involving some 40,000 volunteers and six international conferences dedicated to the drugs. Psychiatrists were using small doses of LSD to help their patients access repressed material (Cary Grant, after 60 such sessions, famously declared himself “born again”); other therapists administered bigger so-called psychedelic doses to treat alcoholism, depression, personality disorders and the fear and anxiety of patients with life-threatening illnesses confronting their mortality.

That all changed in the mid-’60s, after Timothy Leary, the Harvard psychologist and lecturer turned psychedelic evangelist, began encouraging kids to “turn on, tune in and drop out.” Silly as that slogan sounds to our ears, a great many kids appeared to follow his counsel, much to the horror of their parents. The drugs fell into the eager embrace of a rising counterculture, influencing everything from styles of music and dress to cultural mores, and, many thought, inspired the questioning of adult authority that marked the “generation gap.” “The kids who take LSD aren’t going to fight your wars,” Leary famously claimed.

In 1971, President Nixon called Leary, who by then had been drummed out of academia and chased by the law, “the most dangerous man in America.” That same year, the Controlled Substances Act took effect; it classified LSD and psilocybin as Schedule 1 drugs, meaning that they had a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use; possession or sale became a federal crime. (MDMA, which was still being used therapeutically, was not banned until 1985, after it became popular as a party drug called Ecstasy.) Funding for research dried up, and the legal practice of psychedelic therapy came to a halt. But beginning in the 1990s, a new generation of academics quietly began doing psychedelics research again, much of it focusing on people with cancer. Since then, several dozen studies using psychedelic compounds have been completed or are underway. In a pair of Phase 2 psilocybin trials at Hopkins and N.Y.U., 80 cancer patients, many of them terminal, received a moderately high dose of psilocybin in a session guided by two therapists.

Patients described going into their body and confronting their cancer or their fear of death; many had mystical experiences that gave them a glimpse of an afterlife or made them feel connected to nature or the universe in a way they found comforting. The studies, which were published in The Journal of Psychopharmacology in December 2016, reported that 80 percent of the Hopkins volunteers had clinically significant reductions in standard measurements of depression and anxiety, improvements that endured for at least six months.

Other, smaller studies of psilocybin have found that one, two or three guided sessions can help alcoholics and smokers overcome their addictions; in the case of 15 smokers treated in a 2014 pilot study at Hopkins, 80 percent of the volunteers were no longer smoking six months after their first psychedelic session, a figure that fell to 67 percent after a year — which is far better than the best treatment currently available. The psychedelic experience appears to give people a radical new perspective on their own lives, making possible a shift in worldview and priorities that allows them to let go of old habits.

Yet researchers believe it is not the molecules by themselves that can help patients change their minds. The role of the guide is crucial. People under the influence of psychedelics are extraordinarily suggestible — “think of placebos on rocket boosters,” a Hopkins researcher told me — with the psychedelic experience profoundly affected by “set” and “setting” — that is, by the volunteer’s interior and exterior environments.

For that reason, treatment sessions typically take place in a cozy room and always in the company of trained guides. The guides prepare volunteers for the journey to come, sit by them for the duration and then, usually on the day after a session, help them to “integrate,” or make sense of, the experience and put it to good use in changing their lives. The work is typically referred to as “psychedelic therapy,” but it would be more accurate to call it “psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.”

Though the university researchers seldom talk about it, much of the collective wisdom regarding how best to guide a psychedelic session resides in the heads of underground guides like Mary. These are the people who, in many cases, continued to do this work illicitly, long after the backlash against psychedelics during the 1960s ended most research and therapy. But their role in the current renaissance is an awkward one, as I discovered early this spring when I sat in on the nation’s first certificate program for aspiring psychedelic guides.

ON A FRIDAY AFTERNOON in late March, 64 health care professionals of various stripes — doctors, therapists, nurses, counselors and naturopaths — gathered in Namaste Hall at the California Institute of Integral Studies (C.I.I.S.), a school of psychology and social sciences in San Francisco, to begin their training to become legal psychedelic therapists.

To be admitted to the program, an applicant must have a professional medical or therapy license of some kind, and most of the trainees — whose average age looked to be about 45 and whose number included nine psychologists, nine psychiatrists and four oncologists — had enrolled in this certificate program in the belief that psychedelic drugs like psilocybin and MDMA, administered with the proper support and guidance, hold the potential to revolutionize mental health treatment. The career path might not be clear or straight yet, but these people want to be ready to lead that revolution when it arrives — which may be sooner than we think.

It quickly became clear that the reason most of the people in the room were willing to devote the time (five weekends and one full week over nine months) and the money ($7,800) to be certified as a graduate of the program is that they’d been persuaded — often by personal experience — of the therapeutic potential of these compounds. As Manish Agrawal, a rugged 48-year-old oncologist who practices in Maryland, told me, with a sardonic lift of an eyebrow, “You don’t do something like this because you read a magazine article.”

The drugs at the center of the therapy being taught — still classified by the government as Schedule 1 — cannot be used in the training, a limitation that both students and instructors lamented. (C.I.I.S. plans to petition the F.D.A. for permission to give psilocybin and MDMA to students in future trainings.) And while most of the faculty was drawn from the ranks of therapists who work in sanctioned clinical trials of psilocybin and MDMA, because so much of the relevant experience belongs to guides who have been working underground, the program draws on the wisdom of these people too.

Though the program’s explicitly stated intention is to train guides to work in the world of legal psychedelic therapy, that world (apart from the handful of clinical trials) doesn’t quite exist yet, while the psychedelic underground beckons right now.

Janis Phelps, a psychologist and C.I.I.S. administrator who established and directs the program, forthrightly confronted the issue in her introductory remarks to the class Friday evening. “We are training you to be aboveground therapists,” she emphasized. “If you are thinking of working underground” — she later told me a strenuous effort had been made to weed out such people — “you need to think about that. Because we want you to be aboveground, F.D.A.-approved therapists. Everyone engaged in this research is squeaky clean.”

She looked out over the room of aspiring guides. “So I invite you into the tensions of the field as it now exists.”

BILL RICHARDS, clinical director of the psychedelics-research program at Johns Hopkins and the author of “Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences,” is one of the few surviving links between the first and second waves of sanctioned psychedelic research in America. A jovial, goateed psychologist in his 70s with an infectious cackle, Richards led off the weekend’s instruction on Saturday morning.

Working at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center at Spring Grove in the 1970s, Richards and his colleagues successfully treated alcoholics, cancer patients and people suffering from depression with LSD until 1976, when research at the center shut down. “How can this ever have been illegal?” Richards likes to say. “It’s as if we made entering Gothic cathedrals illegal, or museums, or sunsets!”

When research with psilocybin resumed in the 1990s, Johns Hopkins recruited Richards because of his long experience guiding patients during a high-dose psychedelic experience. Today’s researchers work with psilocybin and MDMA because a session tends to be shorter than with LSD and because the words carry much less political baggage. Since the ’60s, LSD has been associated in the public mind with the counterculture and with stories, true or not, of people jumping off buildings thinking they could fly, blinding themselves by staring at the sun or landing themselves in the emergency room after psychotic episodes.

MDMA and psilocybin are less well known and don’t seem to have the same associations. (Also, the fact that psilocybin is “natural” — derived from a mushroom — seems to count in its favor.) Richards has trained many of the guides now working in clinical trials not only at Hopkins but also at N.Y.U. and at Imperial College London.

In his PowerPoint presentation, Richards laid out what has become the standard protocol for aboveground psychedelic therapy, and the role of the guide at each of the three principal stages of “the journey.” First comes a series of preparation sessions, in which volunteers are told what to expect, asked to set an intention (to quit smoking, say, or confront their fear of death) and offered a set of “flight instructions” for the journey ahead.

These generally advise surrendering to the experience, whatever it brings and however disturbing it might become. (“Trust, let go, be open” is one mantra he recommends, or, borrowing from John Lennon, “Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream.”) If you feel as if you are “dying, melting, dissolving, exploding, going crazy, etc. — go ahead.” Richards stressed how important it is for the guide to quickly establish a rapport with volunteers, so that during the session “they can let themselves ‘die’ or go crazy — that requires an awful lot of trust!” Because the patients’ ego defenses are likely to be disabled by the drug, it’s crucial that they feel safe.

The second stage is the journey itself. Richards showed a slide of the Hopkins treatment room, decorated to look like the office of a psychiatrist with an interest in Eastern religion and indigenous peoples, with shelves holding large-format art books and spiritual tchotchkes, including a Buddha and a large ceramic mushroom. The volunteer stretches out on a couch and puts on eyeshades and headphones to encourage an inward journey free of distraction. (Richards has put together a playlist consisting mainly of classical compositions arranged to support and structure the experience.)

Two guides, typically one male, the other female, sit with the volunteer for the duration but say very little, allowing the journey to unfold according to its own logic. Mostly the guide is present to offer a comforting hand if the journeyer is struggling, jot down anything she has to say and generally keep an eye on the volunteer’s physical well-being while she is roaming her psychic landscape. Because it is the drug and the mind that drive the journey and not the therapist, the guide’s role calls for an unusual degree of humility, restraint and patience — the sessions can last for hours. (No snoozing or checking of email; meditating, however, is O.K.) Richards describes the session as the “pièce de résistance” of the work, “in which you’re focused intensely on one human being as if that’s all that exists in the world. It’s a great way to get exhausted!”

The last stage is integration, which typically takes place the following day. Here the guide helps the volunteer make sense of what can be a confusing and inchoate experience, underscoring important themes and offering ideas on how to apply whatever insights may have emerged to the conduct of the volunteer’s life. The challenge, as Richards put it, is to help the volunteer transform “flashes of illumination” (he’s quoting Huston Smith, the late scholar of religion) experienced during the trip “into abiding light” — into a new, more constructive way to regard your self and situation.

It is sometimes said that in the last few decades psychiatry went from being brainless — relying on talk therapies oblivious to neurobiology — to being mindless — relying on drugs, with little attention to the contents of consciousness. If psychedelic-assisted therapy proves as effective as early trials suggest it might, it will be because it succeeds in rejoining the brain and the mind in a radical new therapeutic paradigm: using not just a chemical but the powerful mental experience it can occasion, given the proper support, to disrupt destructive patterns of thought and behavior.

Such a new approach couldn’t come at a better time for a field that is “broken,” as Tom Insel, head of the National Institute of Mental Health until 2015, told me bluntly. Rates of depression (now the leading cause of disability worldwide, according to the W.H.O.) and suicide are climbing; addictive behavior is rampant. Little has changed, meanwhile, in psychopharmacology since the introduction of SSRI antidepressants in the late 1980s. This may explain why prominent figures in the psychiatric establishment are voicing support for psychedelic research.

Addressing a conference on psychedelic science in Oakland last spring, Insel and Paul Summergrad, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, offered encouragement to the psychedelic researchers in the audience, with Insel singling out for praise “the novel approach here” — the way the psychedelic therapist combines pharmacology and psychotherapy to create a single transformative experience.

PSYCHEDELIC THERAPY AS the idea is now understood was developed by a group of researchers working in Saskatchewan in the mid-1950s, including the psychiatrists Abram Hoffer, Humphry Osmond (who, in 1957, coined the word “psychedelic,” which loosely translates from the Greek as “mind manifesting”) and their frequent collaborator and muse, a brilliant amateur therapist named Al Hubbard.

After both conducting and participating in a great many mescaline and LSD sessions — at the time it was routine for scientists to test drugs on themselves — the researchers observed how variable the experience could be, depending on circumstance and mind-set. In those days, no one knew how best to administer these strange new compounds; the need for a guide wasn’t immediately apparent. Some early scientists in white coats bearing clipboards dosed volunteers in a hospital room with white walls and fluorescent lights.

Very often, the volunteers would then be left alone. Researchers didn’t yet understand that the psychedelic experience is not foreordained by the chemical but rather is “constructed” in the mind from an unpredictable mix of expectation, memory, the contents of the unconscious and a variety of environmental factors.

Beginning in the late 1950s, as the researchers began to better grasp the many factors at work, they began to work more consciously with set and setting (though the words wouldn’t be used for another few years), bringing music and images into a treatment room they made comfy and emphasizing the role of a guide.

Shamans have known for thousands of years that a person in the depths of a trance or under the influence of a hallucinogenic plant like ayahuasca or peyote can be readily manipulated with the help of certain words, cues, special objects or music. They understand intuitively how the suggestibility of the human mind during an altered state of consciousness can be harnessed as an important resource for healing — for breaking destructive patterns of thought and proposing new perspective in their place.

One of the Canadian group’s key contributions to psychedelic therapy was to introduce the tried-and-true tools of shamanism, or rather the Westernized version of it that, to one degree or another, most of today’s psychedelic guides still practice, whether working aboveground or below — though the tools of shamanism play a larger role in the underground.

Before my own psychedelic journey, I met and interviewed more than a dozen such guides, many of them trained by the therapists who were using psychedelics in their practices before they became illegal and decided that, rather than give up a tool they had found to be effective, they would continue to work underground, at substantial personal risk. (Beginning in 1971, possession or sale of most psychedelic drugs was punishable by a prison sentence.)

One such therapist was a Bay Area Jungian psychologist named Leo Zeff, perhaps the best-known underground guide of his generation; before his death in 1988, he claimed to have “tripped” 3,000 patients and helped train 150 underground guides, many of whom are still at work.

My travels through the psychedelic-therapy underground convinced me that while the community is obviously far-flung and heterogeneous and has its complement of charlatans, many guides are professionals who share an approach and even a code of conduct. In 2010, a “wiki” for guides appeared on the internet — a collaborative website where individuals could share documents and together create new content — where, for a time, the community appeared to be codifying the rules and standards of the profession. (The site has since vanished or moved.)

On the website, I found a draft charter for would-be guides — “to support a category of profound, prized experiences becoming more available to more people” — as well as links to printable forms for legal releases, ethical agreements and medical questionnaires. (“We don’t have very good insurance,” one guide told me. “So we’re very careful.”) There was also a link to a thoughtful “Code of Ethics for Spiritual Guides,” which acknowledges that “participants may be especially open to suggestion, manipulation and exploitation.

The code stresses that it is incumbent upon the guide to disclose all the psychological and physical risks. (Compared with other psychoactive compounds, psychedelics have low toxicity and are nonaddictive. The risks are primarily psychological: In some people, they can produce short-term anxiety and paranoia and, in rare cases, psychotic episodes. In the current clinical work, an estimated 1,000 volunteers have received psilocybin without a single serious adverse event.) The code also requires that the guide obtain consent, guarantee confidentiality, protect the safety of participants at all times, “safeguard” against ambition and self-promotion and accommodate clients “without regard to their ability to pay.”

Relative to the way guiding is practiced in the aboveground clinical trials (and taught at C.I.I.S.), the underground guides I interviewed, and eventually worked with, take a somewhat more active role in choreographing the experience, bringing into the “ceremony,” as they’re apt to call it, such traditional elements as incense, tobacco and sage smoke, rattles, the singing of icaros (sacred songs) and chanting of prayers.

“There are now two distinct lineages,” I was told by an underground guide with 35 years of experience, who asked me to use a family name, Michelle. “In the Western medical model, the guide is taught never to ‘get ahead of the medicine’ ” — that is, he or she aims for a noninterventionist, back-seat role during the session, and because these are foremost scientific trials, sticks to a standardized protocol in order to minimize the number of experimental variables in play. Many underground guides find this needlessly confining.

“The journey should be customized to each person,” Michelle said. “The idea of playing the same music for everyone makes absolutely no sense.” Instead, she might choose a comforting piece to support someone struggling with a challenging trip, or put on something “chaotic and disassembling” to help break down another client’s defenses. “A healer is not just a sitter. She does stuff.”

Many underground guides have traveled extensively in Mexico, Brazil and Peru to study with traditional healers; Michelle believes psychedelic therapy still has much to learn from the “earth peoples” who have made use of psychedelic plants and fungi in their healing ceremonies for thousands of years. She feels the work she does offers more scope for “creativity and intuition” than the rote clinical techniques being taught aboveground allow.

I WOULD HAVE preferred to have my own guided psilocybin session aboveground in the reassuring confines of a medical institution, but the teams at Hopkins and N.Y.U. weren’t currently working with so-called healthy normals (do I flatter myself?) — and I could lay claim to none of the serious mental problems they were studying. I wasn’t trying to fix anything big — not that there wasn’t room for improvement. Like many people in late middle age,

I had developed a set of fairly dependable mental algorithms for navigating whatever life threw at me, and while these are undeniably useful tools for coping with everyday life and getting things done, they leave little space for surprise or wonder or change. After interviewing several dozen people who had undergone psychedelic therapy, I envied the radical new perspectives they had achieved. I also wasn’t sure I’d ever had a spiritual experience, and time was growing short. The idea of “shaking the snow globe” of my mental life, as one psychedelic researcher put it, had come to seem appealing.

In Mary, I had found an underground guide with whom I felt comfortable. Mary’s approach, in terms of dosage, also happened to approximate the aboveground experience, though she worked with whole mushrooms rather than the capsules of synthetic psilocybin used in the university trials.

“The mushroom teachers help us to see who we really are,” Mary said, as we sat across the altar from each other. “They bring us back to our soul’s purpose for being here in this lifetime.” By now I was inured to the New Age lingo. I was also impressed, and reassured, by Mary’s professionalism.

In addition to having me consent to the standard “agreements” (bowing to her authority for the duration; remaining in the room until she gave me permission to leave; no sexual contact), she had me fill out a detailed medical form, a legal release and an autobiographical questionnaire that resulted in 15 pages of writing it took me the better part of a day to complete. All of which made me feel I was in good hands, even when those hands were flapping a crow’s wing around my head.

On my tongue, the dried mushroom, which was easily four inches long and had a cap the size of a golf ball, was as parched as desert sand and tasted like earth-flavored cardboard, but alternating each bite with a nibble of chocolate helped me get it down. We chatted quietly for 20 minutes or so before Mary noticed that my face was flushed and suggested I lie down and put on eyeshades.

As soon as Mary put on the first song — an insipid New Age composition by someone named Thierry David (an artist thrice nominated, I later learned, in Zone Music Reporter’s category of Best Chill/Groove Album) — I was immediately propelled into a nighttime urban landscape that appeared to have been generated by a computer.

I was experiencing synesthesia, in which one sense gets crosswired with another, so that sound was creating visual space, and what I took to be David’s electronica conjured a depopulated futuristic city, with each note giving rise to another soft black stalagmite or stalactite that together resembled the high-relief soundproofing foam used to line recording studios.

I moved effortlessly through this digital nightscape as if within the confines of a dystopian video game. Though the place wasn’t particularly frightening and had a certain sleek beauty, I hated being in it and wished to be somewhere else, but it went on and on, seemingly forever. I asked Mary to please play something else, and though the mood shifted with the new music, I was still stuck — trapped — in this sunless computer world. Why, oh why, couldn’t I be outside?

This could easily take a terrifying turn, it occurred to me, and with that a dim tide of anxiety began to build. Recalling the flight instructions, I told myself there was nothing to do but let go and surrender to the experience. Relax and float downstream. I realized I was no longer captain of my attention, able to direct it this way or that and change the mental channel at will. No, this was more like being strapped into the front car of a cosmic roller coaster, its heedless headlong trajectory determining moment by moment what would appear in my field of awareness.

Actually, that’s not entirely true: All I had to do was remove my eyeshades, and reality, or at least something loosely based on it, would re-present itself. This is what I now did, partly to satisfy myself that the world still existed but mostly because I badly needed to pee. Sunlight and color flooded my eyes, and I drank it in greedily, surveying the room for the welcome signifiers of nondigital reality: walls! Windows! Plants!

But this reality appeared in a new aspect: jeweled with morning light, every beam of it addressed to my eyes. I got up carefully from the mattress, and Mary took me by the elbow, geriatrically, and together we made the long journey across the loft to the bathroom. I avoided looking at her, uncertain what I might see in her face or betray in mine.

After producing the most spectacular crop of diamonds, I made my unsteady way back to the mattress and lay down. Mary, speaking softly, asked if I wanted “a booster.” I sat up to receive another mushroom, for a total of about four grams. Mary was kneeling next to me, the mushroom in her upturned palm, and when I finally looked up into her face, I saw she had turned into María Sabina, the Mazatec curandera whom I had read about.

Sixty years ago, Sabina gave psilocybin mushrooms to R. Gordon Wasson, supposedly the first Westerner to try them, in a dirt-floored basement of a thatch-roofed house in the remote mountains of Oaxaca. Mary’s hair was now black; her face, stretched taut over its high cheekbones, was anciently weathered; and she was wearing a simple white peasant dress. I took the desiccated mushroom from the woman’s wrinkled brown hand and looked away as I chewed; I didn’t think I should tell Mary what had happened to her.

When I put my eyeshades back on and lay down, I was disappointed to find myself back in computer world, but something had changed, no doubt a result of the stepped-up dose. Whereas before I navigated this landscape as myself, taking in the scene from a perspective recognizable as my own, with my attitudes intact (highly critical of the music, for instance), now I watched as that familiar self began to fall apart before my eyes, gradually at first and then all at once.

“I” now turned into a sheaf of little papers, no bigger than Post-its, and they were being scattered to the wind. But the “I” taking in this seeming catastrophe had no desire to chase after the slips and pile my old self back together. No desires of any kind, in fact. And then I looked and saw myself out there again, but this time spread over the landscape like paint, or butter, thinly coating a wide expanse of the world with a substance I recognized as me.

But who was this “I” that was able to take in the scene of its own dissolution? Good question. It wasn’t I, exactly. Here the limits of our language become a problem: In order to completely make sense of the divide that had opened up in my perspective, I would need a whole new first-person pronoun. For what was observing the scene was a vantage and mode of awareness entirely distinct from my accustomed self.

Where that self had always been a subject encapsulated in this body, this one seemed unbounded by any body, even though I now had access to its perspective. That perspective was supremely indifferent, unperturbed even in the face of what should have been an unmitigated personal disaster. The very category “personal,” however, had been obliterated. Everything I once was and called me, this self six decades in the making, had been liquefied and dispersed over the scene. What had always been a thinking, feeling, perceiving subject based in here was now an object out there. I was paint!

Lots of other things happened in Mary’s room, and in my head, during the course of my journey that day. I gazed into the bathroom mirror and saw the face of my dead grandfather. I trudged through a scorched desert landscape littered with bleached bones and skulls. One by one appeared the faces of the people in my life who had died, relatives and friends and colleagues whom, I was being told, I had failed properly to mourn. I beheld Mary transformed once again, this time into a ravishing young woman in the full radiance of youth; she was so beautiful I had to turn away.

At one point Mary put on one of Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites. It was the suite in D minor, a spare, infinitely sad piece that I’d heard many times before, often at funerals. But this time was different, because I heard it in my egoless, nondual state of consciousness — though “heard” doesn’t do justice to what transpired between Bach’s notes and me. The preposition “between” melted away. Losing myself in the music became a kind of rehearsal for losing myself, period. I let go of the rope of self and slipped into the warm waters of this ineffable beauty — Bach’s sublime notes, I mean, drawn from a cello’s black well of space by Yo-Yo Ma’s mournful bow as it surfed across its strings. I became identical to the music, a word that doesn’t begin to describe the power of what these unearthly vibrations were, or explain how they somehow lifted up and carried me beyond the reach of all suffering and regret.

The sovereign ego, with all its armaments and fears, its backward-looking resentments and forward-looking worries, was simply no more, and there was no one left to mourn its passing. And yet something had succeeded it: this bare, disembodied awareness, which gazed upon the scene of the self’s dissolution with benign indifference. I was present to reality but as something other than my usual self. And although there was no self left to feel, exactly, there was a feeling tone, and that was calm, unburdened, content. There was life after the death of the ego.

THE SUNDAY-MORNING session at C.I.I.S. began with great anticipation — the speaker was Ralph Metzner, who worked with Timothy Leary at Harvard and is regarded as one of the wise elders in the psychedelic community.

Metzner is in his 80s now, and stepping up to the microphone in his newsboy’s cap, he seemed frail. For much of his presentation, he read from one of his books — something about the soul and the six archetypal paths through this life. It wasn’t until the Q. and A. that things got interesting.

A student who identified himself as a psychotherapist asked Metzner to talk about psychedelics, a subject he hadn’t yet mentioned. With that gentle nudge, Metzner proceeded to veer wildly off message, exposing the tensions that Janis Phelps alluded to Friday night but that had been absent from the weekend’s presentations thus far. “These are drugs that psychotherapists unanimously feel could improve psychotherapy,” Metzner began, “but their use is illegal. What does that tell you? Something about the society we live in!”

Metzner paused — and then jumped. “There is a vast underground network of psychedelic therapy, you know — vast. Larger than the approved uses of psychedelic therapy.” He went on: “It’s an underground culture, and underground cultures are good, in fact they can be lifesaving.”

Phelps, her porcelain complexion reddening, stood up, taking a step toward the lectern to solicit another question, but Metzner wouldn’t be deterred. Declaring that we were in the midst of a spiritual emergency in this country, he told the students we have these “fantastically promising medicines that can cure all sorts of ills, and yet doctors can’t get them.”

Metzner’s voice rose. “We don’t have to accept that!” The eminent professor seemed to be inviting his flock to engage in a collective act of civil disobedience. This he likened to the underground in Germany, where he grew up, during the war: “There were German families who took in Jewish families and hid them in their closets.” He voiced impatience with the pace of scientific research and federal approval, “at a time of civilizational collapse,” when we have these medicines that we know work and could help our society right now. “It doesn’t need to be proven over and over again. When there’s a plague, you don’t go through double-blind placebo-controlled studies! It’s a plague!”